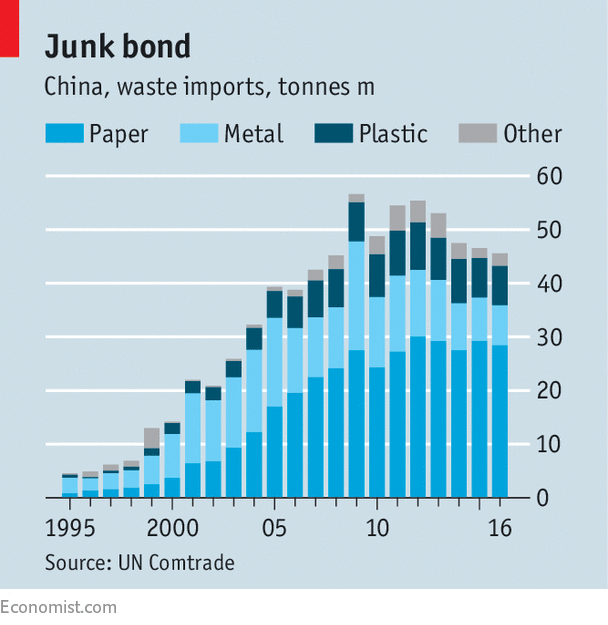

As the world’s largest waste importer, China received more than 7.35 million tons of plastic scraps and 28.5 million tons of mixed paper in 2016, about half of the globe’s total. Coming mainly from Europe, Japan, and the United States through direct or indirect trade via Hong Kong, for decades the products were flushed in China, a country that was willing to take these products, process them, and put them back into the economy. However, on January 1 of this year, that all changed as a ban of 24 types of waste imports went into effect.

A Brief History

Thanks to China’s manufacturing boom, unwanted trash always has a purpose in China. Waste materials can be processed, and (re)used to produce various goods such as clothing, toys, decorations, as well as the packaging for these goods. The trade seems a win-win. Exporters earn a profit by sending garbage to China rather than a local landfill, while Chinese companies get a steady supply of higher quality recyclables, which are much cheaper and easier to process compared to domestically sourced raw materials.

However, as has been highlighted in numerous reports about cities like Guiyu, China’s former e-waste processing capital, this multibillion-dollar industry is a filthy business. Quality issues are a persistent headache for recycling centers. Scrap plastics, paper, metal, and fiber collected from curbside recycling programs often contain too much food waste and other contaminants, thus are not suitable for reprocessing or reusing. Packed and loaded, these imports of recycled materials later enter into roughly 60,000 small-scale Chinese workshops where laborers manually sort out and clean up different types of garbage. The lack of protection and pollution controls in such rural workshops has not only inflicted health hazards to the workers, but also contaminated the air, water, and soil.

Facing mounting public pressure, in 2013 the Chinese government launched the “Operation Green Fence,” a campaign that blocks importation of illegal and contaminated recycled items through aggressive cargo inspections. The new year of 2018 saw the implementation of a “Green Fence 2.0” in China’s waste sector: following a notification to WTO last July, Beijing imposed a ban on 24 categories of low-grade solid waste for recycling, including household plastics, unsorted paper, textiles, and slags. And the war on foreign garbage (a.k.a. yang la ji) is expected to escalate as China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection just announced a decision to enforce stricter limits on the level of impurities in 11 types of waste imports from March.

Impacts on waste recycling in China

The ban is certainly good news for Chinese manufacturers. They will gain access to higher quality materials while passing along the costs of sorting and quality control to recyclers abroad. Moreover, the import ban is conducive to Chinese recyclers. In the wake of the recent decline in overseas supply, surging price will catalyze demand for locally sourced recycled materials and incentivize collectors to capture these wastes for repurposing. As indicated in our previous study, upward pricing pressure will particularly benefit informal workers who can efficiently divert recyclables from other waste streams and sell them to recycling and reprocessing centers at a cheaper price.

Unfortunately, this won’t fix China’s waste conundrum (and its associated environmental problems) easily. Approximately 75% of the garbage used by China’s recycling industry comes from domestic sources, which are dirty and poorly sorted as the imports. Take its plastic industry as an example. Driven by an exploding population, changing consumer behaviors and attitudes toward waste, the country’s plastics consumption is growing exponentially. However, most plastic scraps are either uncollected from source or mixed with other wastes, meaning that they will eventually end up in landfills or incinerators, not recycling plants.

Disruptions to the global industry

The effect of China’s ban has rippled beyond its domestic market. Exporters that rely heavily on China for waste processing are grappling with a buildup of recycled materials. In Canada, Britain, and several European nations, scraps are piling up in recycling centers with nowhere to dump. Since Beijing slammed the door shut, recyclers from the developed world have been desperate to find an alternative. Some look to new shipping destinations somewhere in Southeast Asia or the Middle East, but no single market is comparable to China’s in terms of its size and processing capacity. Others have turned into incineration or landfilling despite its detrimental effect on the environment.

Green Fence 2.0 has struck and will continue striking the international recycling industry. In the short run, recyclers face lost revenue, shipping costs, and demurrage charges. But additional costs are climbing up gradually as the industry is seeing a greater need for investments in new and upgraded equipment, more stringent quality control processes, and better upstream/downstream coordination. In response to that, cities and consumers will have to spend more on the trash they throw away.

Opportunities under China’s ban

Whether it’s in importing or exporting nations, the recycling industry is poised for a change. Tough regulations have raised the bar for everyone and created opportunities for both the recycling business and government to assess their current practices and policies as well as to develop innovative solutions that enable them to flourish under changing markets and technologies. Depending on the categories of waste generated, there is a multitude of measures to handle the commercial, household, agricultural, industrial, and post-consumer wastes in an environment-friendly but economical manner.

Specifically, it’s time for China to challenge its existing waste management system. Since foreign garbage will no longer be an excuse for its failure to clean up the waste mountains at home, both private and public sectors have to find a better way to tackle the challenges. Luckily, with the increasing urban population, growing consumerism, and burgeoning high-tech business, China is already rich in opportunities if it plans to go sustainable.

Over the coming weeks, we will delve further into these parts of the waste management industry and provide insight into the specific areas addressed, outlining case studies, assessing trends, drivers, and solutions as China looks to provide a sustainable framework for its waste management future.

To learn more about the challenges, and opportunities of waste in China, feel free to review some of our other posts on the topic

- http://www.coresponsibility.com/ewaste-informal-system-better/

- http://www.coresponsibility.com/earthworm-farms-solve-food-waste/

- http://www.coresponsibility.com/china-food-waste-management-opportunity/

- http://www.coresponsibility.com/recycled-waste-in-shanghai-where-it-goes/

- http://www.coresponsibility.com/shanghai-landfills-closures/

- http://www.coresponsibility.com/chinas-plastic-waste-epidemic/

Feature Image Credit: Reuters