For our regular readers, you will know that we have been spending last several months looking deep into how waste is managed in China, with a specific focus on how recycled waste is collected, sorted, and processed in Shanghai.

This is driven in part by the belief that Shanghai has, and will, serve as a model for city development in China going forward. It is a city that not only has experienced accelerated population and economic growth, but has quickly grown into one of the fastest growing consumer economies in the last decade. And this growth has presented some unique local challenges and solution providers.

It is a topic where we have spoken at length about material economics, and the actors themselves, but we never told the most important story of all. The story of where all the waste goes.

To learn more about this system, we embarked on a journey. We interviewed informal collectors, tracked down collection sites across the city, and looked at how different materials travel through Shanghai’s waste disposal system. Through this process, we followed over 30 waste samples, including plastic bottles, aluminum cans, cardboard packaging, Styrofoam, iron shelves, copper, carpet, wood, and steel – all materials found in your average household. We focused to learn more about the collection and sorting process (and actors) and the infrastructure for diverting or managing the waste.

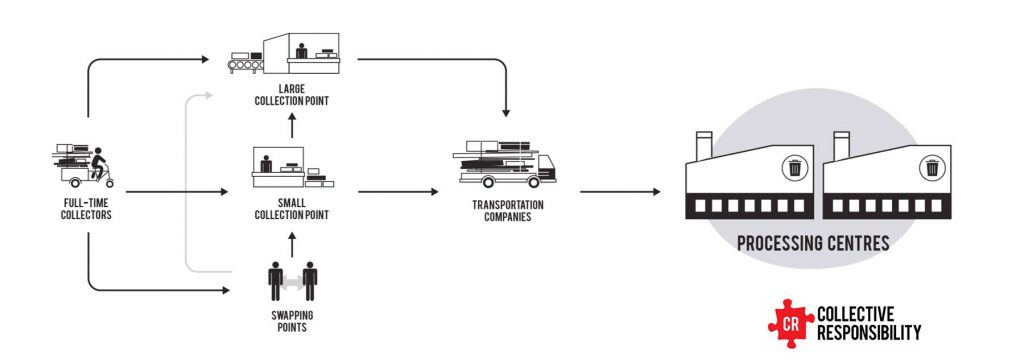

In some cases, while waste without value would be picked up and moved to the landfill by a single company, the route for information was far more complex and almost entirely out of government hands. A private collector would load the waste onto his tricycle, and sell the material to multiple third parties where it gets treated. First, they would ship it to a nearby sorting and collection site, then a waste compressor, a large collection site, a recycling facility, and finally a manufacturer that could reprocess and reuse the waste.

Three treatment processes

Routes were certainly difficult to follow, but over time, patterns began to appear. In particular, the household materials we tracked, which (broadly) found themselves following the path to three treatment processes:

Recycling

Most of the materials we tracked actually went to recycling plants – and with surprising efficiency. Within two to three days of disposal, all of our plastic bottles, aluminum cans, wood, metal, and cardboard packaging went from waste bin to manufacturer. When following the materials into a recycler, or even to a manufacturer who has the ability to take the waste and reprocess it, we were encouraged to find that some materials were able to go from the waste bin into inventory in a week. For some materials, like paper and cardboard, it was fast – at 3-5 days. While for others, like metal, it could take measurably longer.

Incineration

Of the materials we tracked, few went to incinerators. Only some plastic bottles fell into this category. Private collectors sold them to small compressors that crushed and flattened the bottles. Then the material is burned in incinerators and its ashes were disposed of in government landfills. Shanghai currently owns five incinerators but is determined to build more over the next few years. As they shift away from landfills, Shanghai will expand facilities by a significant margin – building eight new incinerators by 2020.

Landfill or Dumping Site

Only carpet went directly to landfill. Private collectors and government contractors would pick them up and sometimes shipped them to sorting sites. But they eventually would settle for landfill treatment. Some of the landfills we found were government-run, but others were either private or unregistered, looking more like roadside dumping sites. Shanghai’s government currently operates five landfills but will close two by the end of 2017.

Case Study: Recycled Cardboard

Across all three treatment groups, one material captured our attention: cardboard. A material that has grown exponentially in its use and has an environmental footprint that includes water, forests, and chemicals. Furthermore, as we found out, it has one of the most established collection and recycling processes.

After collecting some packages, we flattened a few boxes into single cardboard sheets and called a private collector inside the building to pick it up. He paid for our cardboard pile, which proved that cardboard was a material with economic value, and removed any residual tape. Then, he loaded it onto his tricycle. Over the course of the next few hours, we watched this process continue, until his tricycle was fully loaded. Once full, he made his way to a large collection center, where he was paid by the center manager for the weight of the materials. Just over 400kg.

At that point, the collection center took the materials off the tricycle. After a simple compression and wrapping process, the large cardboard bundles were loaded onto a flatbed truck. Once the truck was full, it proceeded to drive to a paper and pulp factory, a public listed cardboard factory selling paper and packaging material to shipping companies, just outside the city limits.

Looking at the satellite image of the company’s site pictured above, there were a few features that immediately stood out. The most important being the left-hand side of the image is dominated by white and beige colored stacks, which meant there are hundreds of stacks of cardboard and paper sheaf waiting to be reprocessed. And the other being the two large factory buildings on the right, and roughly four storage facilities on the left, all indicative of large-scale manufacturing.

Recycling Trends

Through this research, and interviewing dozens of actors in this economy, there were a few major takeaways:

- China’s private waste collectors are fast and highly efficient when it comes to recycling – sending tons of household waste back to manufacturers.

- Recycling in China is not something subsidized by cities but is driven by the economic value of materials. If material waste has value, it will find its way to a manufacturer.

- There is an entire ecosystem of companies, that are in need of, and ready for, a steady flow of material to be delivered on a daily basis. Materials that are, in part largely sourced from the household and commercial wastes of the city, and are being diverted from landfill.

- So long as there is high demand for raw material, private collectors will search street corners, construction sites, and waste bins to find anything they can sell. Thus businesses with recycling plants and expertise will continue to be valuable.

For more articles on this topic, check out our Waste in China tag. Follow Collective on social media to receive updates on our latest articles, reports, and events.