THE QUESTION: IS CHINA GENEROUS?

Much of our work here at Collective centers on the business side of “social entrepreneurship” in China – going beyond business as usual to work towards the development of a better world. Yet, we also run into a certain question from the more philanthropic side of that mission: Is China generous?

Answering such a loaded question risks overgeneralizing a country with nearly a billion and a half citizens of dozens of ethnicities, backgrounds, languages, and beliefs. Instead, let’s reframe the question while taking a closer look at the context of philanthropy in China and general generosity must operate.

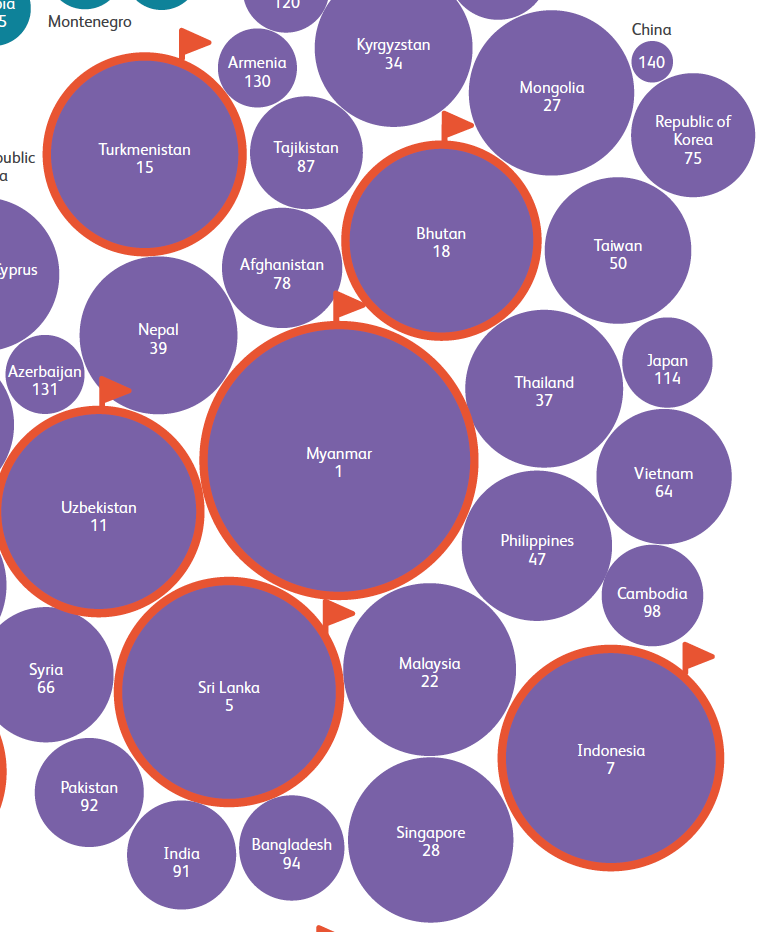

Many have attempted to capture “the Chinese view on generosity” by putting numbers to it. Most recently, the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) issued their 2016 Giving Index in October, in which they ranked 140 countries on various measures of “generosity,” using parameters like helping a stranger in need or donating money. The finding that China ranked in last place on the global spectrum made headlines, causing many to wonder what about the country makes it seemingly so averse to giving.

But here at Collective, we specialize in demystifying trends in China’s market at the society level. As is often the case, we need discuss the context surrounding what the CAF survey findings suggest.

Let’s take an alternative look at the culture of philanthropy in China. There’s more to it than meets the eye.

HISTORY AND CONTEXT

To start, overall giving in China has long been facilitated at the macro-level. A top-down approach has characterized much of the donation culture, with portions of employees’ paychecks automatically pooled together for corporate donations, making individual giving compulsory rather than voluntary. This hierarchical structure applies in volunteering as well, with leadership making executive decisions to dedicate the time of subordinates for a cause, instead of individuals volunteering their downtime.

But wait: there’s more to it.

“Quid Pro Quo Philanthropy”

Check out this clip on corporate donations in China, from #AskTheCollective Episode 003:

For those who did give as individuals – often the wealthy elite and/or executives – an unspoken agreement of mutual benefit influenced giving as well. The reality of “quid pro quo philanthropy” implied that donating to a notable cause would earn a meeting with political leadership, advancement in the bureaucracy, prestige, etc. Something would be given, and something would be expected in return.

While there’s nothing inherently wrong with this top-down, give-and-take system of giving, by not engaging with citizens as individuals, China’s philanthropic culture was limited to the executive level.

The 2008 Earthquake, and What Changed

When the 2008 earthquake hit Sichuan province – causing over 130 million USD worth of damage and displacing 4.8 million people – the Chinese masses gave a historic outpouring of aid. Domestic public donations hit unprecedented levels, reaching 877 million RMB in aid within 48 hours of the disaster. Giving was not just financial either, as volunteers stepped forward in droves to help the victims as well.

The generosity was there.

Additionally, corporate donations were expected and measured against each other, but for once, employees faced peer pressure at the individual level, too. Rankings of donations were passed around publicly – and of course, no one wanted to end up last on those lists, upping their contributions accordingly.

The Red Cross Fiasco and Donor Expectations

With the sudden influx of aid and giving, the Red Cross Society of China was well-positioned as the leading charity to receive and manage proceeds. However, this new ground for China proved rocky for both the donors and the organization.

For starters, there was a disconnect in expectations: Most of the funds raised went to the Chinese government to support reconstruction and development in the wake of the disaster, rather then directly aiding the victims – which, while beneficial, was not where the average citizen intended for their donation to end up.

Public discontent worsened with the reveal of the Guo Meimei scandal, in which proceeds not only failed to reach benefactors in need, but supported a scandalous affair.

Misappropriation of funds in a time of increased public engagement ultimately resulted in overall mistrust of charities and foundations, hurting other organization besides the Red Cross. Since 2008, fundraising has taken a hit in China as many NGOs work to rebuild the trust that was betrayed over 10 years ago.

SYSTEMIC CHALLENGES & REALITIES OF PHILANTHROPY IN CHINA

With this history in the back of our minds, let’s take a look at what barriers to philanthropy in China today. How and why people do people give money in general, and why can’t we directly compare China with other countries today?

The answers lie in protective policies, social infrastructure, and perceptions of giving.

1. Protection Laws & Policies

What many countries take for granted is the existence of bystander protection policies, such as “Good Samaritan” laws. If you witness someone in need who might be injured or endangered and decide to step forward and help them out, you might be heralded as a hero.

But in China, that very stepping forward into the situation might expose you to the risk of being sued or extorted by the victim.

Many cases have demonstrated the unfortunate negative repercussions some face in return for their altruism – as well as tragic cases of resulting negligence from bystanders in fear of this risk. Shanghai recently instituted a Good Samaritan law in November, but reversing attitudes towards random acts of kindness will take time. For many, offering aid is simply not worth the risk of personal endangerment.

On a similar note, making charitable donations as an individual, from religious tithing to sending funds to NGOs, might earn you a tax break or other incentive in other countries. However, in China, it wasn’t until a new charity law went into action last year that charitable giving would offer would-be donors with any tax benefits.

Yet even this is policy works at the business level rather than the individual, offering up to 12% in corporate income tax waivers for donations. For individuals, the positive incentive still simply isn’t strong.

It remains to be seen how these new policies will influence China’s standings in the CAF 2017 Index – which will be the first to use the 2016 data.

2. Social Infrastructure

Looking back at the CAF giving survey, many of the “most generous” countries have high or majority populations of the Muslim, Buddhist, or Christian faiths. For many, giving donations and tithes to religious centers doubles as supporting the local community.

Additionally, many of the high-ranking countries in the Middle East are currently experiencing war and conflict on a daily basis. A crisis of social need and collective endangerment prompts a unique response among the average individual. For many in these situations, it’s “stand together, or not at all.”

China, on the other hand, is far more secular and continues to work towards growing its economy during a time of peace. The relative lack of external threat and other motivators for community giving can lower drive for individual generosity.

3. Perceptions of Giving

What some might call “donations,” individuals in China might not give a definition at all. Family and community ties do garner mutual support, financial or otherwise – and as in the case of “quid pro quo philanthropy,” quietly helping a neighbor can be seen as an investment towards a future need for help in return.

Even at the corporate level, disclosing degrees of charitable giving is even kept hush-hush rather than openly talked about. Many opt to keep donation amounts and frequency discrete.

Furthermore, the Chinese government has a very active role in supporting the welfare of its citizens. Practically a “safety net” to its citizens, it offers many necessary social services and aid through the income the population already gives. Here, a top-down approach overcomes the necessity for individual engagement upon which other countries rely.

HOW CAN WE UNDERSTAND THE CONTEXT OF GIVING IN CHINA?

At the basic level, people give to causes they care about, whether due to sympathy or empathy – personal connection motivates generosity.

One area in which China differs from other countries in the CAF index is the notion and power of community. Community ties are certainly strong here, but recent geographic and demographic shifts have called into question what counts as one’s “community.”

China is currently in the middle of one of history’s largest migrations – by 2020, an additional 300 million people are expected to move from the rural regions of central and western China to the eastern metropolises. Where rural roots of communities held strong in the past, urban centers unravel and reform connections between strangers from across the country’s provinces and cultures. As the masses reforge their idea of “community”, it will take time to reach the same level of trust and unity as that of the past.

NGOs often help foster this forging of new relationships at the macro level by providing platforms, centers, and causes for people to care about. However, NGOs attempting to gain a foothold in China face several obstacles, from bureaucracy to policy barriers, to the little trust from the public – which is still hesitant about “charitable organizations” in the wake of the 2008 incident. NGO laws have the potential to make or break an organization’s potential for gaining public support.

Check out this clip on starting a charity in China, from #AskTheCollective Episode 004:

WHAT CHANGES ARE NEEDED TO FOSTER IMPROVED PHILANTHROPY IN CHINA?

Ultimately, five key areas will need to see considerable shifts for philanthropy in China to thrive in 2017 and beyond. We all bear responsibility for achieving change – across stations, sectors, and industries.

- Shift the top-down approach to philanthropy in China, and instead support voluntary giving of time, money, and effort at the individual level. With China’s vast citizen base, stimulating the masses can promote exponential growth of active generosity for the country’s benefit.

- Protect and support potential donors and volunteers through implementation of more Good Samaritan laws and increased positive reinforcement through tax incentives.

- Support small and medium NGOs by lowering barriers to entry and supporting those crucial first steps in gaining trust and traction.

- Professionalize the industry of giving by setting clear and reasonable expectations between organization and individual donors. Then, meet those expectations through accountability, transparency, and open communication. Both donors and benefactors need to understand the pipeline and process for giving – and receive guarantee of promises being met.

- And ultimately, broaden our understanding of China’s nuanced context of giving. Looking past surface statistics, we are responsible for opening our minds to a more holistic view of the environment in which China’s government, citizens, and organizations operate.

You might also be interested in our reports on CSR in China and Social Innovation in China. Follow Collective on social media to receive the latest updates on articles, videos, and events.

This article was written by Gabrielle Williams, Research Analyst at Collective Responsibility.