As the work of NGOs in China has developed over the last 15 years, especially in the years following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, the role of social media platforms critical to support public engagement in charitable activities.

Like many areas of the wider economy where digital platforms disrupted traditional forms of engagement, while there were many upsides to the transitions, there were also challenges.

Challenges which have forced NGOs, donors, and platforms, to make adjustments, and through this post, we will share some insights into a few recent charity scandals to show the impact of mismanagement and how that has led to calls for higher levels of transparency and accountability within the third sectors.

Case 1 – Shidichou Crowdfunding Platform

With the shift toward online engagements, dozens of crowdfunding platforms supporting donation campaigns have launched. These campaigns have given NGOs access to millions of new donors and created vibrant marketplaces for a wide range of beneficiaries.

As providers have crowded into the space, the challenge of ensuring the quality of submissions has grown. For the largest platforms, like Tencent and Alibaba, each submission is supposed to be reviewed, and verified but the platforms prior to the launch of the funding campaigns. Unfortunately, with the large number of campaigns being submitted, platforms have failed to be consistent in policy, and that has led to a number of high profile scandals.

Most recently, Shuidichou, a popular platform launched in 2016, was challenged by donors who were concerned that funds were not used as advertised. The case came to light in November 2019, when Shuidichou sent so-called “volunteers” to hospitals in more than 40 cities across China to promote their APP and help patients to open their crowdfunding accounts.

These “volunteers” also helped the patients to set fund-raising targets, some of which were far higher than what the patients would need, which lead to questions about the role of commissions paid to “volunteers”.

“I used love to donate to support those people through these platforms, especially when you see their poor photos. But I started to doubt myself these days after seeing these news, I don’t want them to take advantage of me.”

To answer the questions raised, Shuidichou established a crisis management team, to investigate the case, , and committed to improved transparency measures.

Case 2 – China Children and Teenager’s Fund

As the level of donor education improves, and their standards elevated, donors are taking a more proactive approach to supervising donations and the progress of programs they have donated to.

This change in donor expectations is something that many NGOs have struggles with, as seen in the December 2019 crisis involving the “Spring Bud” program, of the China Children and Teenager’s Fund. A program launched in 1989 to help girls in poverty areas return to school.

In December 2019, when the “Spring Bud – Female Students Tuition Fee Support” program update was loaded to its Alipay platform, donors began asking why 453 of the 1,267 beneficiaries were boys when the program was advertised as exclusively helping girls.

The Foundation initially responded by saying that boys in poverty areas were also in need of assistance, and thus the reallocation was appropriate. The response did little to address the concerns, and soon after, they were forced to issue a second statement stating that the funding for the 453 male students would be returned to the donors.

Case 3 – Sichuan Red Cross Firefighters Fund

At the core of a donor’s decision to make a donation is trust. Trust in the organization’s capacity to do the work, its team to execute on their promise to donors, and in how the organization will use remaining funds.

In most cases, the problems are rooted in simple mistakes, a failure to effectively communicate, or in a gap of expectations between donor and organization. Problems that can be exacerbated by poorly trained staff, who may be acting with the best intentions.

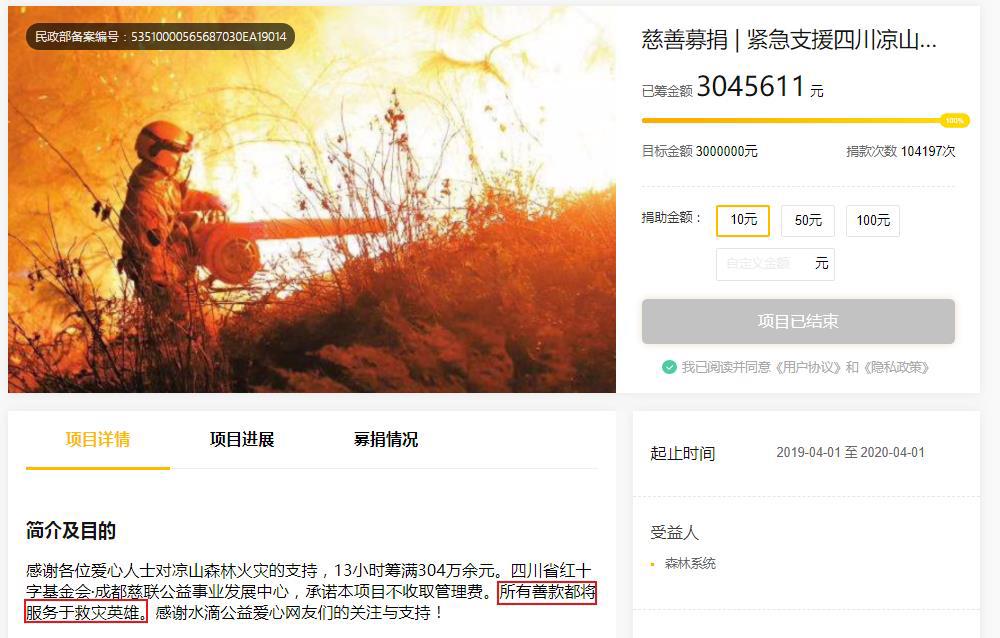

In 2019, the Sichuan Red Cross Foundation was challenged publicly about their management of a fund dedicated to support the families of 30 fire fighters who were killed in the Liangshan fire disaster.

As part of the campaign, all funds were said to be given to the families of the heroes. However, donors found through online documentation, that more than half of the funds were used to develop different programs. Programs that were related to firefighters, but different from the one donors had given to.

Donors who felt their donations had be diverted inappropriately, and without their consent, took to social media.

“I think the photo, title and the program description mislead people. The overview said all the amounts will go to support the 30 fire fighters’ families.”

Like the previous case, the root of the issues was not that the funds were being improperly used, not that the NGO failed to support the group they promised to. It was rooted in the inability, or unwillingness, of the organization to communicate honestly with donors about the over-funding and how they planned to use those funds.

Through the online calls for accountability, the foundation was forced to respond quickly with an apology, and explanation of how the decision was made, and a commitment to use all the donations to support the 30 fire fighters’ families.

Conclusion

With the speed of growth in China’s third sector propelled by the growth of online funding platforms, the chances for failure were high. Particularly in an environment where public perceptions of NGO practices were already damaged by previous high-profile scandals.

These examples for us are three that we feel highlighted the risks that new platforms face, but more importantly how they are responding to the crisis by building better practices, communicating better with donors, and holding NGOs accountable for their work.