With the recent news that China’s domestic coal consumption was understated by up to 17%, a renewed debate has begun about China’s data quality and ability to keep its commitments to reduce CO2 and other greenhouse gases (GHGs). A debate that is only intensified by the fact that China has been trying to proactively position itself as a leader at the World Climate Summit in Paris.

For us though, while carbon and climate change are important topics, the real issue that we feel China is facing is the long-term security of its energy, and the ability to maintain economic growth with coal as its primary fuel source.

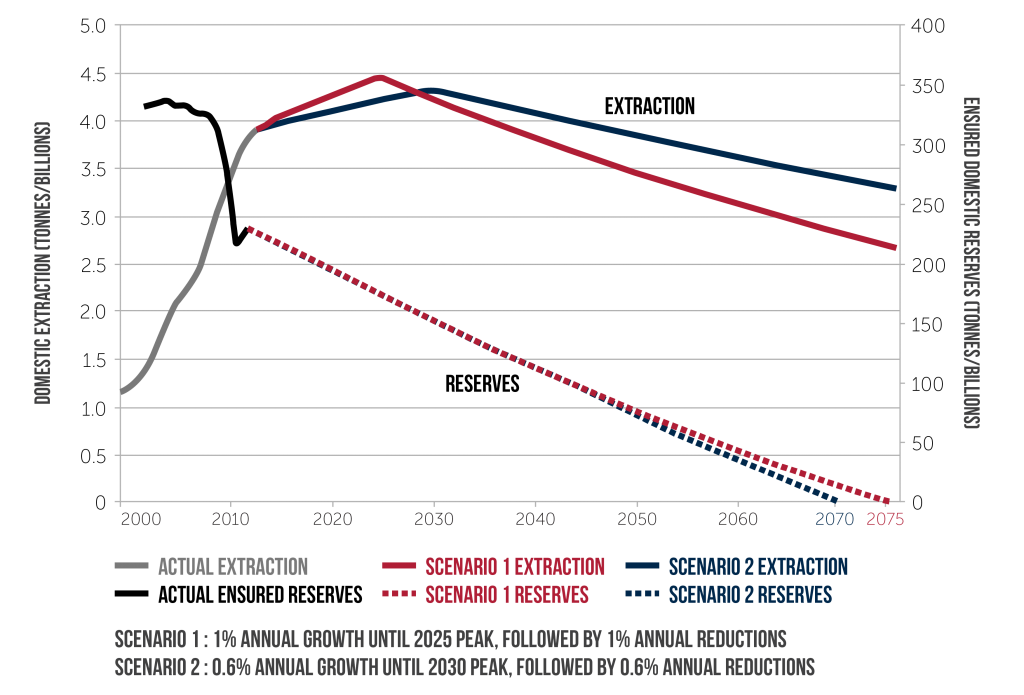

A challenge that we have illustrated through two simple models that plot China’s proven reserves against two scenarios for coal consumption going forward. Both of which show that even with consistent reductions after extraction peaks the lifetime of China’s provable coal reserves is short.

Very short.

Using this chart as a representative guide for coal reserves over the next 50 -100 years, it is apparent that regardless of commitments made to the international community, in the near future China is going to have to make different choices about the way it will power its economy.

Despite that, over the last few years, one of the biggest trends in global coal has been the rise of China to the top of global coal imports, this is not a solution to China’s long-term energy problems. Neither is investing billions into installing wind and solar capacity, which have been largely left idle due to the distance from, and resistance of, the grid.

So what are China’s options?

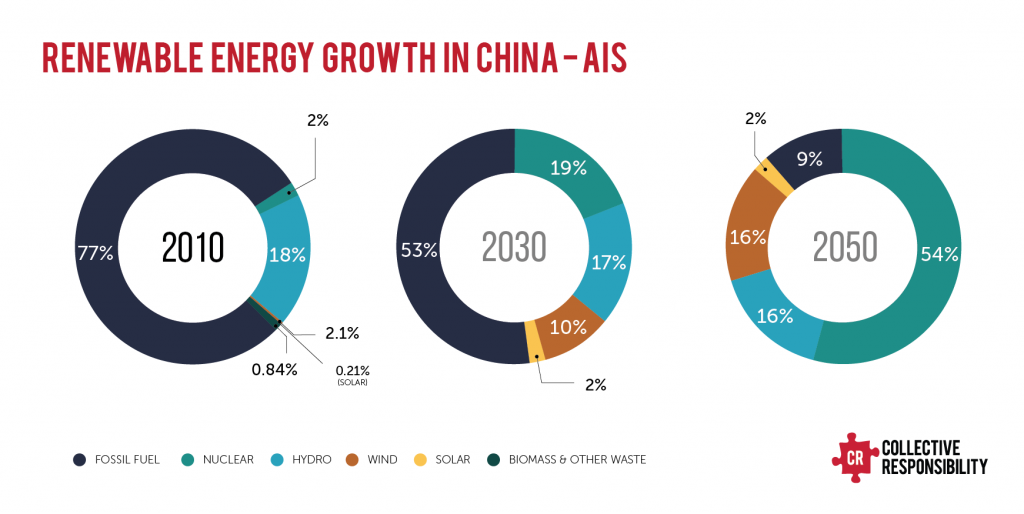

For China to achieve the scalability required to meet the energy demands of 300 million more urban residents by 2030, then changes in economic structure, energy efficiency, and large-scale investments in nuclear power are going to be required.

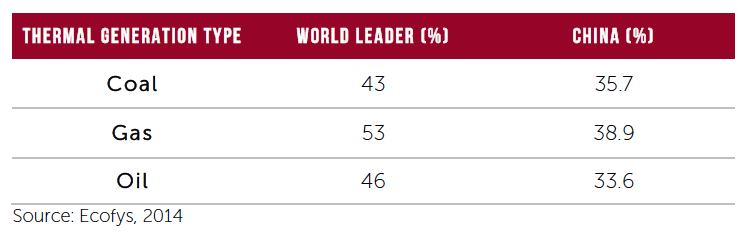

It has long been the Chinese government’s policy to reduce energy intensity, as outlined by the previous two 5-year plans, but on inspection of China’s efficiencies against worldwide best available technology (BAT) it reveals much can be achieved in the area, particularly for natural gas and oil, where heavy investments to boost supply are being made.

Such restructuring has begun with a greater push for the alternative fossil fuels and renewables. Cuts in the coal industry have taken place in response to these changes, with Heilongjiang Longmay Mining Group announcing that it will cut 100,000 jobs over the next three months.

Such restructuring has begun with a greater push for the alternative fossil fuels and renewables. Cuts in the coal industry have taken place in response to these changes, with Heilongjiang Longmay Mining Group announcing that it will cut 100,000 jobs over the next three months.

Despite these market changes, even the most aggressive modeling scenarios to 2050 require major increases in China’s nuclear capacity if coal is going to be suppressed and energy security secured. Even in this “best-case” scenario, coal is still an integral part of the energy mix and assuming China’s rivers remain full, hydro will provide valuable support.

China’s coal situation has forced the hand of the nation to move towards a more service-based, tertiary economic structure. The new normal for Chinese energy demand will have higher proportions from these industries. Even with this shift, total energy demand in 2050 is expected to be a multiple greater than today. As a result, internal policy towards price will have to change in order to boost such areas, which will help improve the ROI for investments in both renewable energy supplies and efficiency programs whilst at the same time altering consumer behavior.

China’s coal situation has forced the hand of the nation to move towards a more service-based, tertiary economic structure. The new normal for Chinese energy demand will have higher proportions from these industries. Even with this shift, total energy demand in 2050 is expected to be a multiple greater than today. As a result, internal policy towards price will have to change in order to boost such areas, which will help improve the ROI for investments in both renewable energy supplies and efficiency programs whilst at the same time altering consumer behavior.

In the end, one thing is for certain, that regardless of whether it is the result of a carbon tax or through diminished reserves, China needs to move quickly away from its reliance on coal-fired energy. Investments in efficiency need to come first, so as to bend the demand curve away from its current growth trajectory, while at the same time bringing the online significant stock of renewable energies.

This is the challenge for China going forward, but an opportunity for firms. Firms who not only have solutions to bring into China but for those who understand the narrative going forward and develop to provide more efficient economies.