While many western cities and firms are scrambling to find solutions and workarounds for the mountains of waste plastic, unsorted paper, textile, and slag that can no longer be sent to China, the Chinese government just doubled down on January’s waste ban with an announcement that over the next 18 months there will be an additional three stages to the existing ban.

It is an announcement that has yet to be covered by the press, but given the size and scale of the feedback that followed the first ban, it is imperative that these stages are understood in their context and application so that firms can adapt strategically (and tactically) to the impending changes.

China’s Waste Ban: A Bit of Background

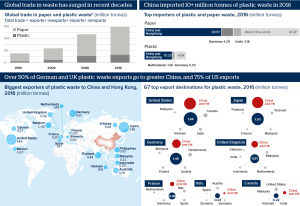

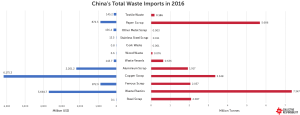

To fuel its rapidly growing economy, China started taking the foreign waste in the 1980s, and over the decades to follow China represents a significant market for recyclers across the world. In 2016 alone, it accepted more than 43 million tonnes of waste, including 70% of the global plastic scraps and 37% of the unsorted paper.

But this is changing after China announced last year that it would no longer be world’s dumping site. China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) raised the minimum required contamination level from 1.5% to 0.5% – a standard that is nearly impossible to reach given current sorting and quality control processes, making it a de facto ban on scrap imports. Targeted wastes are the most polluting types, ranging from household plastic waste and unsorted paper to recycled textiles and vanadium slag.

The ban left the western recycling industry in chaos, causing massive stockpiles of trash from docks in Hong Kong to recycling plants in Australia, Canada, the U.K., and the U.S. Some developing countries are taking more waste overseas, but no other countries have the same recycling capacity as China does. Chinese recyclers are also feeling the pain. Particularly, small and less efficient companies are being squeezed out of the market due to the steep drop in recycled materials, increased competition over scarcer resources, and rising prices of domestic wastes.

The Next Stages

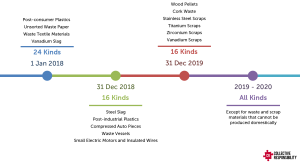

While the last four months have proven challenging to many who were totally reliant on China to take (and process) their waste, on 19 April 2018, China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment (formerly know as Ministry of Environmental Protection) issued a further ban on 32 kinds of waste imports that are typically generated through industrial processes. 16 materials that will be prohibited from 31 December 2018 include steel scrap, compressed car pieces, scrap ships, post-industrial plastics waste, and e-waste. By 31 December 2019, China will reject the importation of wood, cork, steel, and precious metal scraps.

Yet this is not the end goal for the Chinese government. According to Xinhua, China will phase out imports of all solid wastes except ones that cannot be sourced domestically by the end of 2019. To enforce the waste bans, Beijing has launched “Blue Sky 2018,” a ten-month campaign scheduled to run through the rest of 2018, aiming to enhance the inspection and crackdown on the imported scrap materials that violate the country’s quality standards. Only in the first quarter of this year, China’s customs seized 110,000 tonnes of smuggled wastes.

Why the Sudden Change

The multi-billion-dollar waste trade grows a lucrative recycling and processing industry in China. However, the lack of effective supervision and proper waste management practices has caused serious environmental and health problems. Shutting down the door on imported waste is expected to starve the unregulated private mills, thus helping clean up the polluting industry.

Another driver of China’s waste ban is a broader ambition – Made in China 2025. Inspired by Germany’s Industry 4.0, the central government initiated this strategic plan in 2015 to upgrade Chinese manufacturing industry and move it up the global supply chain. The plan identifies the goal of increasing the proportion of core components and materials that are sourced domestically to 40% by 2020 and 70% by 2025 in priority sectors, such as automotive, aviation, and robotics. The newly released waste ban would push producers and manufacturers in these high-tech industries to get raw materials from local sources.

The Next Step?

China’s waste ban has struck and will continue striking the developed world. The stockpile of waste in exporting countries has resulted in an outpouring of complaints, moreover, requests on clarified quality standards and a buffer period. In light of that, Beijing may relax the contamination levels on certain materials temporarily to ease local supply shortage. Unclear about the quality standards, provincial governments have to stop all imports for now, but are likely to accept shipments of high-quality scraps after the policy is well digested and executed.

Alternative recycling market is also expanding to fill the void left by China. The import of waste plastics soars in Southeast Asia where regulations and legal systems on waste management are still immature. But their refusal to take foreign waste can happen any time as environmental regulations catch up and local recycling industry develops.

More importantly, this represents a great opportunity to address the root causes of the challenge: Cities push the waste management problems offshore rather than putting recyclables back into the local economy; Manufacturers build their business around the linear model of “take – make – waste.” China’s waste ban should be a wake-up call for governments and businesses to close the loop, prioritize sustainable practices, and even go beyond recycling to invest in reduction and reuse.

Feature Image Credit: Flickr user baselactionnetwork.