Earlier this week, Shanghai’s municipal government uncovered 100 tons of waste dumped illegally near Chongming Island. Pictures of the scandal garnered serious attention on Weibo and included biohazards, household waste, and plastics in one of Shanghai’s four reservoirs. Investigators from Chongming’s Water Source Management department have found no signs of serious contamination, but they have temporarily halted drinking water from the Dongfengxisha reservoir.

The ongoing clean-up will likely take up to two weeks, but a crackdown on illegal dumping could take considerably longer. For now, Shanghai authorities have labeled two ships responsible for the scandal and have placed suspects in custody.

Many view this story as just one part of a tragic pattern of events: Companies run out of landfill space, search outside the city center, and ultimately dump tons of material in lakes and reservoirs.

In order to understand Shanghai’s problem and prevent future scandals, we need to delve a bit deeper.

In this article, we’ll look closely at Shanghai’s waste management system and answer three questions:

- Is this scandal unprecedented?

- How has Shanghai’s municipal government responded?

- What has prompted these incidents, and how can we prevent them?

Past Scandal

To Shanghai residents, this scandal is nothing new. In August 2015, trucks transported over a thousand tons of household waste from Shanghai to Jiangsu province’s Wuxi.

Likewise, in July 2016, authorities uncovered 20,000 tons of waste in Jiangsu Province’s Taihu Lake. Multiple trucks smuggled construction waste from Shanghai to the neighboring province, which prompted a serious response from China’s Environment and Waste Management Bureau.

Government Response

Following the most recent scandal, Shanghai officials set new guidelines for construction sites. These include mandatory sorting rules and new efforts to limit landfill waste. Under the new guidelines, construction sites must sort waste by treatment method, so recyclable products can go to a reprocessing center and construction sediment can go to a landfill or incinerator. Companies must sort their waste to partner with government contractors, and those that effectively separate recyclables from landfill material are even eligible for a disposal discount.

Waste transport companies who receive government contracts are also subject to stricter regulations. In order to collect sediment and material from construction sites, they must first receive a government permit and register their own landfill in Shanghai. The District City Appearance and Greening Bureau then monitors this landfill on a regular basis.

These guidelines are all new. Shanghai only introduced them in September, and it remains unclear how closely companies will follow them.

The future of non-construction waste is equally as uncertain. In Shanghai’s 13th Five Year Plan, the city announced potential recycling sites in Taopu, Putuo District, Jiefang Island, and Minhang District, as well as emergency disposal sites in Fengxian and Pudong International Airport – but these promises have yet to bear fruit. Landfill space remains scarce, and sorting rules are still in the earliest stages of implementation.

A Structural Problem

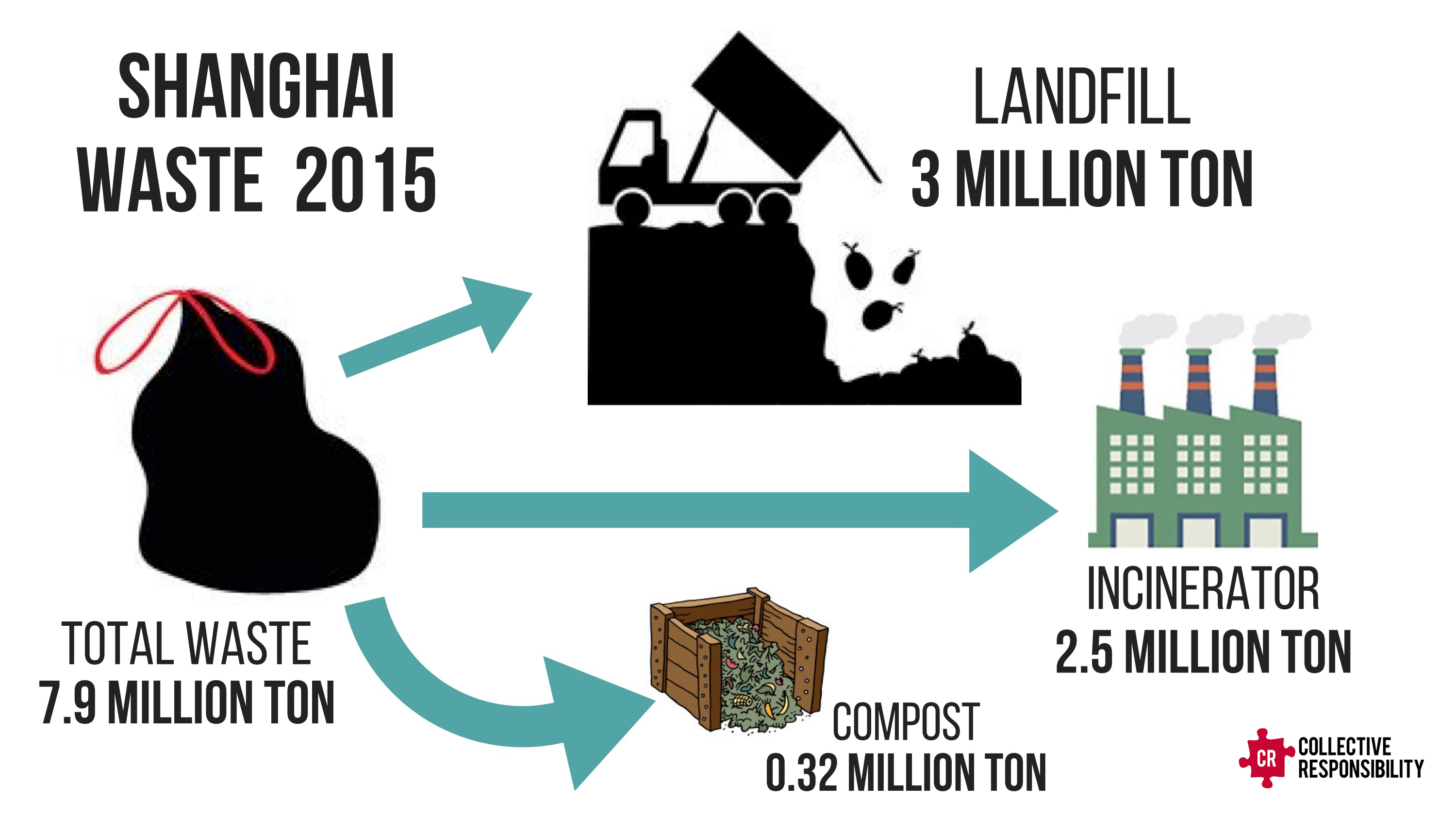

In 2015, Shanghai’s government waste collectors managed 7.9 million tons of trash. Of this total, nearly 3 million tons went directly to landfill, and 2.5 million tons went to incinerators (CNBS, 2015). Only 0.32 tons received compost treatment.

These statistics place the city’s challenge in context and reveal a clear structural problem: Shanghai’s government does not recycle. The 13th Five Year Plan, which applies from 2016 to 2020, announced potential recycling sites, yet it failed to address a more immediate problem – landfill closures. By the end of 2016, the City Appearance and Greening Bureau intends to close two of Shanghai’s five government landfills and has not planned any new sites in the interim.

Essentially, Shanghai’s municipal government has taken too ambitious an approach to this problem. If officials approve five recycling sites, they will likely take years to build, and waste collectors must adjust to a whole new norm. If formal collectors have no incentive to sort material and send up to 40% of their trash to landfill, they are unlikely to adjust operations.

In the short term, this means more waste with less space to put it.

Taking away government landfills does not change sorting habits, reduce waste, or change the way companies collect trash.

Instead, it removes officially regulated landfill sites and forces government collectors to dump elsewhere.

Opportunities for Growth

Shanghai’s problem is a long-term one, but requires an immediate creative solution that achieves three goals:

Incentivizing Sorting

In September, Shanghai released new categories for construction waste and price incentives to separate sediment from recyclable material. This strategy could easily transfer to non-construction waste, offering both punitive and positive incentives to sort waste. For instance, households and businesses could receive tax breaks or reduced disposal costs if they sort recyclable, compostable, and landfill material, and housing developments could face penalties if they fail to sort material. This process will most likely require more government monitors who can inspect household and commercial waste collection centers.

Creating Landfill Alternatives

Shanghai’s municipal government has already considered this step. While construction and household waste are not likely in good enough condition for resale or recycling, they can be reused. Biodegradable and sediment material can become a cheap resource and does not necessarily have to stay in a landfill. Instead, the government can sell or distribute the material for urban landscaping or backfilling.

Working with Informal Collectors

In Shanghai, many non-government affiliated waste collectors manage Shanghai’s recyclable waste. They collect any material that can be reused or reprocessed and sell the material to recycling centers outside of the city. If Shanghai’s government collection wants to start recycling, it should either partner with these waste entrepreneurs or study efficiencies in their collection system. Under this partnership scheme, private waste collectors could sort and sell material to the government, and official collection centers could recycle the material at government-run recycling factories. This way, waste management could remain profitable, sorting could become systematic, and the government could monitor all stages of collection for environmental impact.

For more information about Shanghai’s waste management system, check out our Waste Landing Page, and stay tuned for more analysis.

This article was written by Alison Schonberg, Research Analyst at Collective Responsibility.