When 400 migrant workers were discovered living below an upscale apartment complex in Beijing last week, it was another sign of just how high housing costs have become in China’s largest cities, and the lengths that some are driven to in finding a place called home.

Known as shuzu or “rat tribes” by the locals, the discovery represents an estimated 1 million people living in a warren of Cold-War era tunnels and bomb shelters built beneath the city in the 1950s. And the shuzu are not alone.

Chinese cities are increasingly home to hundreds of thousands of low-income recently graduated university students who turn to makeshift accommodation, living in boxy cramped windowless rooms with shared bathroom and kitchen facilities. Known as “ant people,” this student demographic gets its name from being likened to ants; living in underground colonies, intelligent and hardworking, yet anonymous. Ant people view living in these underground bunkers as a temporary measure, with the ambition that they will eventually find jobs related to their university degrees and might earn enough to money to live above ground.

But for rat tribes, the hukou system whereby migrants can’t buy homes in urban areas is still a huge barrier to them building lives in the city, leading to additional economic and social barriers to integration. Both groups represent a growing trend among the lower income urban demographic who are being forced to live in makeshift accommodation in cities where house prices are skyrocketing.

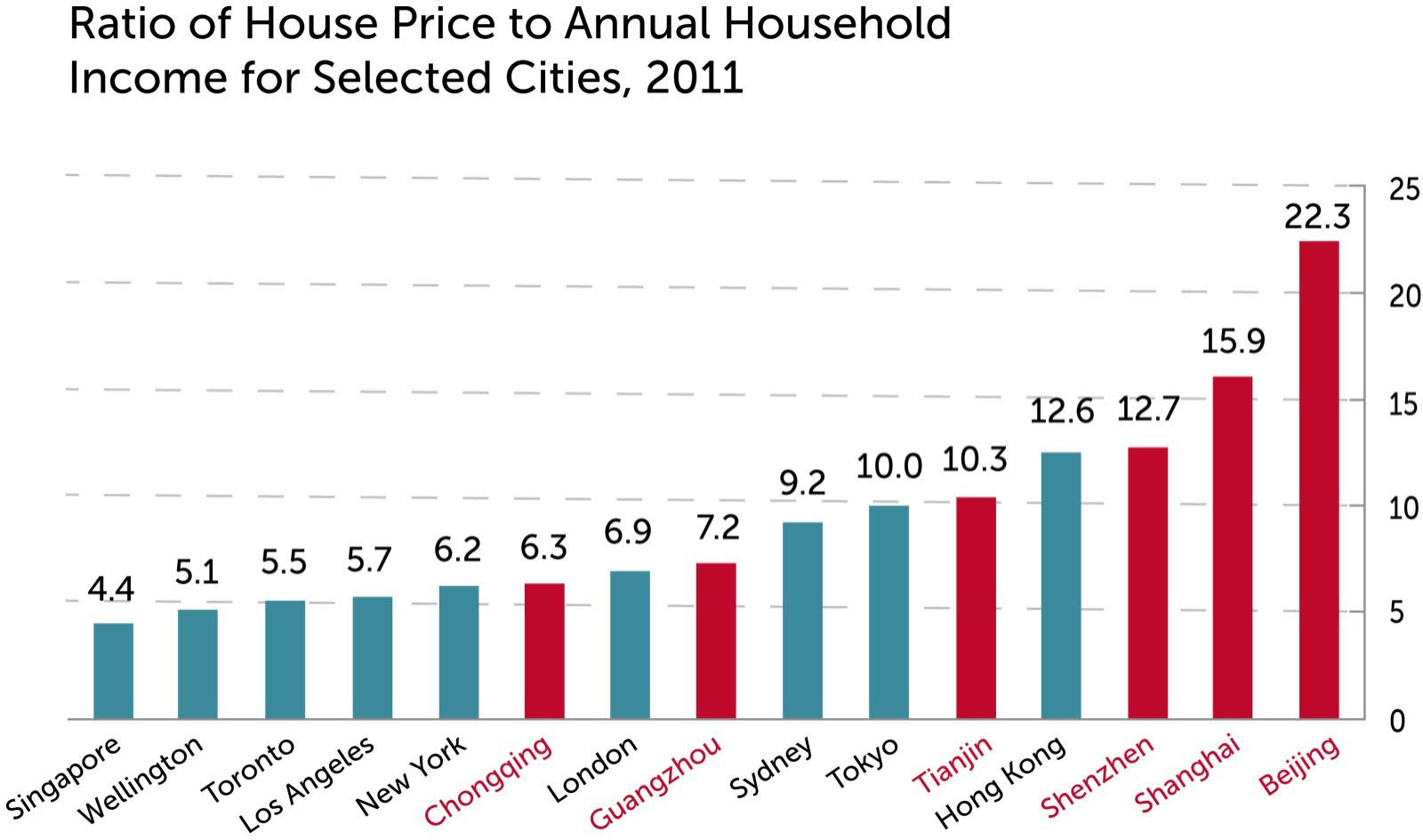

With estimates that in Shanghai it costs 15.9 times the typical household income to buy a standard home, while in Beijing the ratio is even higher, at 22.3, it is no surprise that many have started to look for living space below ground.

Cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin are unusual in the amount of underground space that exists, a requirement for every new building. Still in place today, this is the result of a cold war defense strategy beginning in the 1950s. Aside from the car parks, garages and warehouses, this underground space provides accommodation to a displaced population, and an entire informal rental housing market has sprung up around it, with subterranean dwellers now occupying 13% of all underground space in Beijing. In 2015, more than 120,000 people were evicted from the disused air raid shelters in one incident alone, leaving the question of where will these people be housed?

The rat tribes and ant people now represent an increasingly urgent challenge for Chinese cities to find ways to house and integrate its growing urban population.

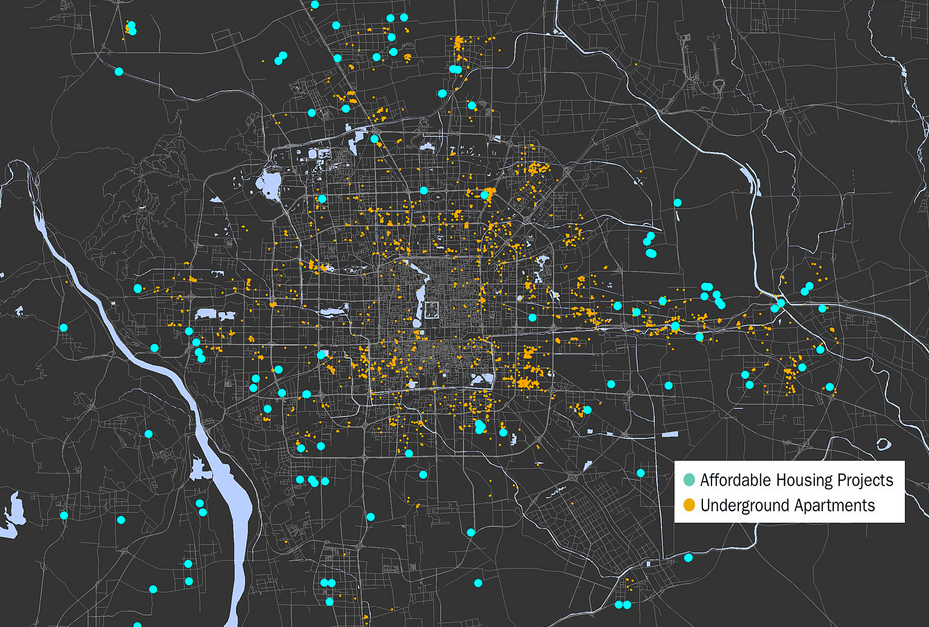

A recent study mapped out the underground rentals in Beijing based on a collection of over 7,000 online ads for underground rental spaces between 2012 and 2013.

Although underground, these bunker apartments are in highly desirable central locations of Beijing, providing an affordable alternative to the areas on the far reaches of town, which means a two hour plus one-way commute to work. Rural migrants who have moved hundreds of miles from their home villages to the big cities of China to find work do not possess an urban hukou and therefore lack the access to public housing and other social welfare services offered to urban residents, which pushes them to live in the very outskirts of town.

So, for many, they turn to basement accommodation which allows them to live much closer to where they work. Surprisingly though, these bunker apartments are not the cheapest option for migrants. A government study of migrant housing in Beijing found that 48.1% of migrants spend less than 300 RMB per month on rent (Xie & Zhou, 2012). With the underground apartments average rental price coming in at 448 RMB, due to the primacy of their location, these underground apartments are more expensive than above-ground apartments located on the outskirts of town.

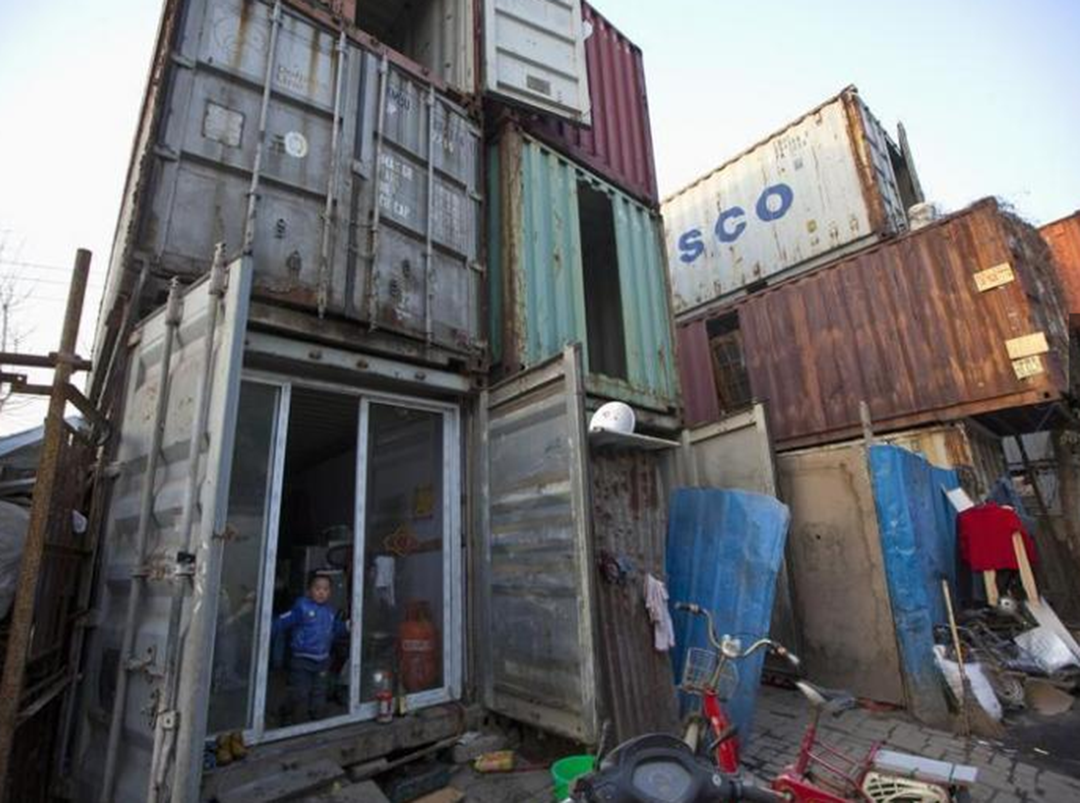

Beijing is not alone in the struggle to house its growing population. In Shanghai, migrants earning a living as waste collectors, delivery service men, and construction workers have taken to living in disused shipping containers on the outskirts of town.

While the issue sheds light on the ever-rising rental prices of China’s first-tier cities for its residents, it also gives insight into a much larger socio-economic challenge for the future of Chinese cities: how to fully integrate the millions of rural migrant workers who have flocked, and will continue flocking to urban areas to find work. With China’s cities expected to be home to around 1 billion people, or 70% of the entire population (McKinsey, 2015) by 2030, the pressure for cities to adapt is mounting.

With many looking towards hukou reform as the answer to accommodate the millions of migrant workers now living in Chinese cities, the increased population burden, along with the steady increase in house prices means that hukou reform alone is unlikely to resolve the issue.

For China, it will be a long and slow process of a rebalancing of the regional economy that will reduce the burden on its first-tier cities, as job opportunities and more affordable housing in interior provinces lure people away from the coastal megacities.

The real conversation then, is how long will it take before the costs of living in the city outweigh the benefits? With increased regional economy in cities like Chengdu, Chongqing, and Zhengzhou, along with large-scale manufacturers that employ hundreds of thousands of migrant workers already making the move inland, the economic gravity in China is shifting. With this shift brings added incentive for millions of migrants in first-tier cities to find employment nearer to the home provinces they migrated from, closer their families, and opportunities to live a much more comfortable lifestyle than the crowded cities.

With accelerated urbanization, the main driver of China’s future economic growth, how to provide affordable housing in cities will remain a major challenge to China’s urban dream.